Unlocking Human Potential:

Antifragile Conflict &

Negotiation Strategies

In this post, CIIAN’s CEO, Warren Hoffman, explains how the concept of antifragility can be applied to conflict and negotiation strategies. Click to listen to the audio or find the transcript below.

Audio Transcript:

Here I’m going to talk about the concept of “antifragility”; specifically in terms of negotiation and conflict but you’ll find the concept and principles can be applied to any aspect of your life.

Now, the essence of antifragility has been known for ages. For example, some 2000 years ago, Seneca is referenced as saying: No tree becomes rooted and sturdy unless many a wind assails it. For by its very tossing it tightens its grip and plants its roots more securely; the fragile trees are those that have grown in a sunny valley.

Or, you might be more familiar with the expression: that which doesn’t kill us makes us stronger. Which as we’ll see, unfortunately, isn’t always the case. Yet this underlying idea that adversity and challenges can lead to strengthening, to growth, is fairly common. Yet the concept hasn’t received much attention, from a technical perspective anyway, until Nassim Taleb, an author and statistician, whose body of work focuses risk, probabilities, randomness, and uncertainty, thoroughly unpacks the concept. He not only unpacks this general idea but comes out the other end with a remarkably eloquent, yet sophisticated concept, blending philosophy with mathematics, into a new concept that he refers to as “antifragility”.

Antifragility is both a technical concept and at the same time, a general principle that can be applied to any aspect of your life. Whether it’s how to allocate your investments, your health regime, or how to structure your business so that it not only survives unknown shocks but thrives from them.

So let’s dig in now, starting with getting a clear idea of what antifragility is. You’ve likely already gathered that antifragility is the opposite of fragility, but what exactly does that mean?

One example Taleb provides to illustrate antifragility is by comparing the mythical creatures of the Hydra and the Phoenix. When the Phoneix dies, it rises from the ashes to live again. While if you cut off the head of the Hydra, it grows two more heads. The Hydra becomes stronger from the damages inflicted on it.

That’s the general idea and is emphasized in the subtitle to Taleb’s book on the topic; Antifragility, Things that Gain from Disorder. The Phoenix didn’t gain from the injuries; yet, it is resilient because it is reborn. It withstands the damages and lives again. Yet the Hydra is antifragile. Unlike the Phoenix, it not only survives the damages but it actually becomes stronger.

Take exercise as another example. When you lift weights, you damage your muscles. When they repair, they don’t return to their original state, like the Phoenix, but rather the muscles become stronger, like the Hydra’s response to damages.

That’s the concept. So thanks to Taleb’s work, we now have three categories to describe the response to volatility and disorder. It can break (which is fragility). It can remain unchanged (resiliency). Or, in response to the volatility, it can become stronger (antifragility).

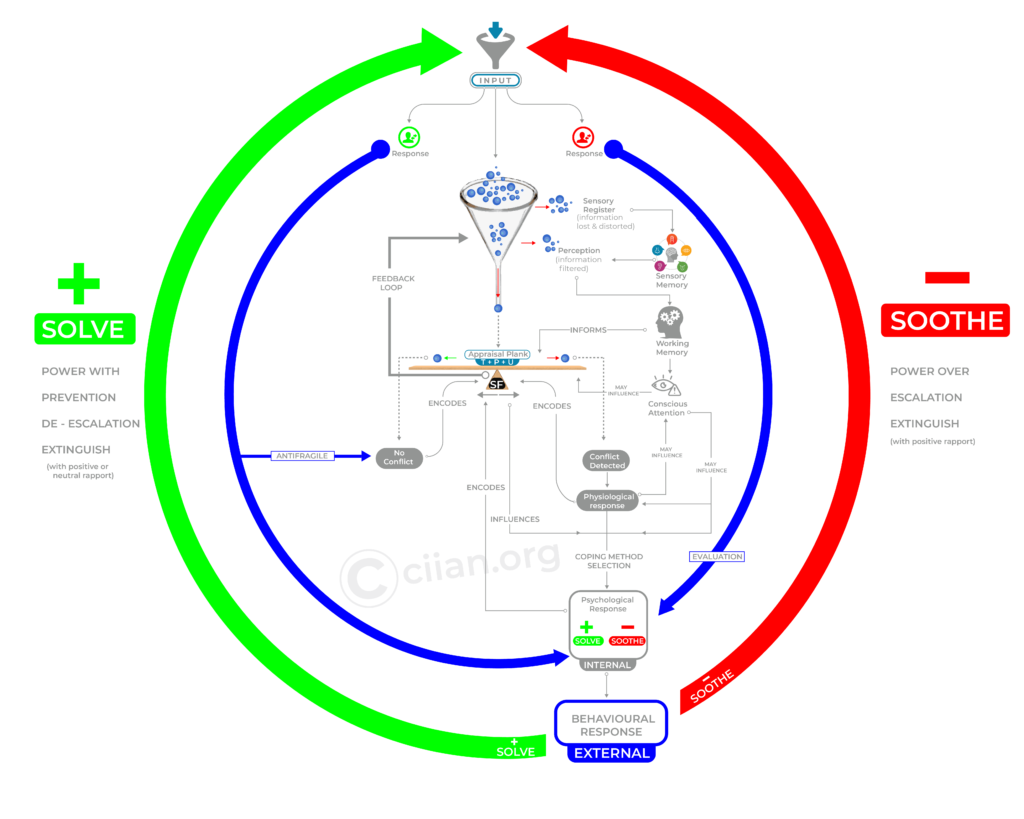

Now, if we consider conflict to be the volatility we experience in life, the volatility that can exist in relationships, within the workplace, between countries and different groups of people, whatever the context, the concept of antifragility can demonstrate the necessity of good conflict management practices.

The way that a conflict is managed, whether an individual’s personal coping style, or a manager’s efforts within the workplace, or even a mediators efforts to end political conflict, the methods and management styles used can result in the very same three responses: fragility; resilience; and antifragility.

Conflict can increase fragility, such as building resentment between people, increasing workplace toxicity or damaging our self-image. So fragility can increase. Or, there might be no noticeable effects from the conflict, so we can be resilient to conflict. Conflicts erupt but are dealt with so that there’s no noticeable gains or losses, there is resiliency, over the short-term anyway. And finally, we can become antifragile with respect to conflict. Conflict can foster growth. New and better solutions. Healthier relationships and so on.

Unfortunately, many of the strategies that are used to address conflict don’t lead down this path to growth, they don’t lead to antifragility. And here’s how it happens.

The key is that antifragility requires exposure to the stressor. The muscle needs exercise to grow. The hydra needs its head cut off to grow more. Similarly, people need exposure to conflict to become antifragile.

And you’re probably thinking, well who doesn’t experience conflict; it’s inevitable. But important differences can occur through the type of coping and conflict management styles used. What happens is that exposure to the true root of the conflict can be missed. The symptoms are addressed, while the root of the conflict is overlooked, and it’s through this error that the opportunity for exposure is missed.

This is quite common. Whether it’s an inexperienced mediator, a manager throwing Band-Aids on a workplace dispute or consider personal conflict coping styles for example. When someone faces conflict, they may target the symptoms of the conflict, in this case the emotional discomfort, and remain sheltered from the deeper origins of the conflict. For example, someone that is experiencing hurt or embarrassment, may try to soothe that emotional discomfort by intimidating and overpowering the other. Take bullying. The act of bullying terminates the conflict and soothes the ego but it does little to address the root cause of the conflict – the original trigger remains.

Or, rather than overriding those painful emotions by using an aggressive approach, some might cope with the emotional discomfort by avoidance; tactfully dodging the topic or pretending there isn’t an issue at all. This, of course, isn’t especially healthy as it may lead to low self-esteem and an increase in friction with others.

In both cases, like the Phoenix, they’ve survived the conflict and, in a sense, rise from the ashes to live another day; yet without exposure to underlying issue, there is no possibility for growth. So the coping styles shelter them from the true roots of the conflict, while soothing the internal discomfort the conflict created. Overreliance on these strategies can become quite a problem over the long term. Unfortunately, many people aren’t even aware of what type of conflict coping strategies they rely on.

The same dynamics can occur for any type of dispute, whether it’s workplace conflict, political conflict, family disputes, any conflict whatsoever. It’s common to have grievances resolved, yet you’ll soon find out that they were only superficial fixes. The symptom of the dispute is addressed, and provides some temporary relief, but there’s a deeper rooted personal or structural issue that’s overlooked.

In all cases, exposure to the root of the conflict is missed. Either through poor coping strategies of an individual, or through the misguided efforts of leaders and conflict practitioners, the root persists, allowing conflict to fester and ultimately re-emerge. We then get a cyclic conflict cycle with a high probability of increased intensity in future disputes as frustrations increase.

So that’s some theory around antifragility in the context of conflict. Personal growth; reconciliation; robust and sustainable agreements; these can only be achieved through proper exposure to the root, which can be quite easily missed based on personal coping styles, the conflict management practices of leaders and managers, or the expertise of a mediator.

You can consider this with respect to your own life or workplace. Look for clues for poorly managed conflict. If there is antifragility, you’d expect a welcoming of conflict as an opportunity for growth. Conflict is an ally. Conflict is an opportunity for new solutions and for strengthening relationships. So attitudes about conflict is great indicator.

If conflict is feared. If conflicts re-emerge. If dissenting views are frowned upon. If there’s significant distrust, gossip, and a general toxic workplace; it’s likely that conflict is being managed poorly. So consider the dynamics along the spectrum of fragility. If things are getting worse, it suggests fragility. If things are stagnant, remaining about the same, it suggests resilience; yet improvements can be made. Conflicts that are being addressed properly can lead to antifragility – so gains can be made from the disorder.

Now, we’ve only just scratched the surface here. As mentioned earlier, Taleb takes this concept to great depths; fully unpacking it, complete with mathematical proofs. We’ll leave the math out and present a few other general principles that Taleb suggests as methods to increase antifragility. I’ll give some general applications within the context of negotiation and conflict, but again, keep in mind, you can apply these to any aspect of your life.

Okay, the first principle on becoming antifragile is to become less fragile. So as a primary step, you want to identify and remove fragilities. We’re looking to limit the downside here. We want to put a cap on risks. So do some brainstorming and thoroughly consider where you (or the process/your business/the system, and so on) – where is it vulnerable?

Within the context of conflict, a good starting point is considering sticking points and triggers. Look for your own personal triggers, or for those in others (whether an individual or a group) and take actions to address and mitigate that threat in advance, before it causes harm. Right, we’re reducing fragility; we’re working to eliminate the potential for failure; the potential for violence; the potential for the process to break down – whatever failure looks like in that particular context.

Conflict is path-dependent. What happens in the past matters. We can’t “unbreak” a glass, so to speak. Once the damage is done, it’s difficult to be undone. Things like regaining trust or regaining respect can take considerable time to be rebuilt. So preventative measures can be exceptionally worthwhile to avoid collapse.

So, identify fragilities and remove them.

Next, look to increase redundancy and optionality.

Taleb warns of systems that are highly efficient and over optimized. Although increased efficiency might create short term benefits, the system is ultimately fragile. Think of a highly efficient factory line, supply chain, or a company overly dependent a few specific leaders, if one critical component fails, the entire system can break down. Overdependence on critical components of the system can lead to failure. Increasing options, and in some cases redundancy, like having two kidneys instead of one, is a safeguard that reduces fragility.

Now, in the context of conflict; consider coping or conflict management styles. Most come to rely on one or more favoured techniques to handle conflict. Yet, if we learn to diversify our conflict strategies to use the right tool for the job, we can get better results.

As a negotiation strategy, dig deep and get creative to find alternative options to your BATNA, which is lingo for your “best alternative to a negotiated agreement”. In other words, before a negotiation, you want to know what you can achieve away from the table – what’s your best alternative. But really, the term should be pluralized. We should be considering our best alternativeS, so multiple options, opposed to just one. This would be more aligned with an antifragile negotiation strategy.

Consider redundancy too. Create multiple paths to reach your objectives. When you pitch them to the other party, one of the alternatives presented may resonate with them more; so you’re more likely to reach an agreement. Find ways to have all roads lead to Rome, as they say, and let the other chose the road that they’re most comfortable with.

Also consider redundancy in communication. Although being succinct is beneficial, at times, conveying important information through multiple frames or different communication channels can be essential. Especially in times of conflict, during heated exchanges, there’s a lot of noise that bogs down communication, so it can be difficult to get your message through.

So, optionality and redundancy. Get creative and work them in, however you can. Finally, let’s consider Taleb’s barbell strategy. Picture a barbell, with weights on each end and the bar you grip in the middle – your standard run of the mill barbell. The general idea of this strategy is that we want to allocate our efforts or resources at the extremes, represented by the weights at the two ends of the bar, while avoiding the middle ground, represented by the actual bar.

This is best grasped through Nassim’s explanation of a barbell investment strategy. He suggests that you put the bulk of your funds, say 90 percent, into something very safe, like cash. Then, to create the barbell, the remaining 10 percent is put at the other extreme, in something very risky yet that exposes you to the potential for maximum gains.

That middle ground, the middle of the bar, is too murky for Taleb, and he suggests it should be avoided altogether. As a past options trader and statistician, he’s aware of the computation errors that occur from risk analysis. He suggests that we can’t prepare for the unexpected, something he calls “Black Swans” – which, is also the title of another one of his bestsellers.

What does his barbell strategy achieve? Well, if you think back to the first principle presented, it was to remove fragilities. The barbell limits fragility because you can only potentially lose 10 percent, it limits the downside. Yet it also builds in the opportunity for large gains. So, in other words, it’s an antifragile strategy.

Now, although this applies nicely to an investment strategy for how you might allocate your portfolio, the general principle can be applied to nearly any aspect of your life. Another example Taleb provides is by playing it safe in a stable job, while moonlighting as a writer, which has less certainty of success but large potential payoffs – if you get a bestseller. So we have the bulk of time in the safe pursuit, the stable job, while at the other end engaging in something that might lead to huge success. The middle ground is avoided.

You can also keep the barbell in mind as a negotiation strategy or in the dispute resolution process. Just like investments, you can organize your efforts, the issues, or even the parties interests along the barbell continuum. You then have some general guidelines on how to allocate your resources.

When approaching it, first look to identify the 3 components. If it is a negotiation strategy, you might organize your interests, the things you want to achieve, into those that are very important to you, and then a few big ticket issues that would be the icing on the cake, something that would lead to a very successful outcome for you. So you have the two weights, dedicating the bulk of your time to the essentials and some of your efforts to the “big ticket” wins. Yet, you also want to identify the middle ground, those issues that are of less concern to you, those you are willing to make concessions for. And by granting those concessions, it will establish a cooperative tone, which will likely help achieve your overall goal.

If you’re facilitating, mediating, or leading a project, you might organize tasks or issues around: complexity; or the potential to move the process forward; or their potential to build consensus, to reach an agreement. You could focus the bulk of your time on the less complex/safer issues, continually achieving small wins, while periodically returning to the tough nut to crack, the key issue or to winning over the key players that will provide the most traction.

So we can organize the issues and interests, the tasks, whatever it may be, along the barbell, then allocate resources accordingly, or vary our strategy based on where it falls on the barbell.

And with that, we’ll wrap this up. Now this isn’t an exhaustive list, just a few ideas to whet your appetite on how you might apply this concept as a decision tool to help approach negotiations and conflict in general. And I encourage you to think about using it to open up your thinking about any facet of your life.

Identify and remove fragilities. Create redundancy and optionality. And finally, consider “barbelling”, if possible. Focus on the extremes. Extreme safety while creating exposure to the potential of a more higher risk, albeit, prosperous return at the other end. And avoid the murky middle ground if possible. Then allocate your resources, whether it’s your time, effort, personnel, money, whatever it may be, along those lines.

But, above all, pay particularly close attention to conflict coping and management styles. Are you, your business or your workplace, fragile, resilient, or antifragile to conflict?

When we are equipped with adequate conflict and negotiation skills to handle conflict appropriately, so when we achieve antifragility with respect to conflict; we can create incredible opportunities that you don’t want to miss. Rather than remaining stagnant, or having conflict slowly erode our most meaningful relationships, we want to embrace conflict as a tool for growth.

As Taleb says: “you want to be the fire and wish for the wind”.

The concept of “antifragility” is built into our conflict training models.

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular article! It is the little changes that produce the greatest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

Im thankful for the blog. Really Great.